The “Marie-Antoinette” watch No. 160

by Emmanuel BreguetNo discussion of the work of Breguet would be complete without the story of watch No.160, known as the “Marie-Antoinette”, a watch that is unique both in its technical ambition and in its colourful history.

According to an oral tradition first written down in the late nineteenth century, around 1783 Breguet received a remarkable order from an officer of the queen’s guard, who commissioned him to make a watch with every complication and sophistication then known – in other words with every complication then possible. There were no limits on either the time or the cost involved in its making. Wherever possible, gold should be used instead of any other metal. The identity of this man remains a mystery. Was he really an officer of the guard, or was it perhaps the king himself? Or was he a member of a group who hoped to set a trap for the queen by drawing attention to her wild extravagance, as with the notorious ‘Affair of the Diamond Necklace’? No one knows. Breguet was doubtless the watchmaker of choice because – although he was still at the beginning of his career, having set up his business less than ten years earlier – he already had a number of important inventions to his name, in particular the perpétuelle watch, and he was the acknowledged specialist in repeating pocket watches. He was modern in his outlook, he had new ideas – and he was discreet. The watch would therefore be self-winding, a technique that Breguet alone had completely mastered at this period; the principle of automation fascinated the eighteenth century and its philosophers, who saw in watchmaking a miniature version of the universe, and of its creator, the Great Watchmaker. ‘Every possible complication’ meant first and foremost all the astronomical and calendar information possible, including the day, date, month, leap years and equation of time. It also meant an extremely sophisticated chiming mechanism and a host of other refinements.

Basically, Breguet was asked to compress a cathedral clock into a few square centimetres. He set to work, and the eventual result was to be the fabulous watch No.160 that would not be completed, after numerous interruptions, until 1827, under the direction of his son Antoine-Louis.

An unprecedented challenge

Basically, Breguet was asked to compress a cathedral clock into a few square centimetres. He set to work, and the eventual result was to be the fabulous watch No.160. There would be lengthy interruptions to the process – during the Revolution, for instance, his most urgent concern was his own survival – and he was to die four years before it was at last finished, in 1827, under the direction of his son Antoine-Louis.

With watch No.160, he had created a masterpiece that would outlive him and that would play a major part not only in his own life, but also in that of his watchmaking firm for many years to come – and even to the present day.

The watch that company records refer to as a “gold watch” or “Perpétuelle minute repeater with perpetual equation of time and jumping seconds” survived the Revolution, which was fortunate given that the workshops were ransacked after Breguet had found refuge in his native Switzerland.

In 1809, Breguet decided to start working on it again, but it was in 1812, 1813 and 1814 that he really made progress: in 1812, 284 and a half days of work were devoted to watch No.160, followed by 228 and a half in 1813 and 212 in 1814. It should be remembered that in the last years of Napoleonic rule, Breguet was unable to export anything, as France was at war with all her neighbours, and French watchmakers were therefore far from overwhelmed with work: what better way to spend his time, while waiting for the fall of the emperor, than in returning to a job that was not only such a technical challenge but also charged with so many memories?

After 1814, when the watch was nearly finished, came another interruption which was to last until August 1823. Determined to complete his masterpiece, Breguet spent the last month of his life working on its finishing touches. In September, he died, and it was another four years before Antoine-Louis Breguet was finally to finish it, in 1827. It should be stressed that it was of course a collective enterprise, demanding all the skills not only of Breguet and his son but also of a team of some twenty colleagues, including notably Michel Weber, one of the firm’s most brilliant watchmakers.

EVERY POSSIBLE COMPLICATION

EVERY POSSIBLE COMPLICATION

That meant first and foremost all the astronomical and calendar information possible, including the day, date, month, leap years and equation of time. It also meant an extremely sophisticated chiming mechanism and a host of other refinements.

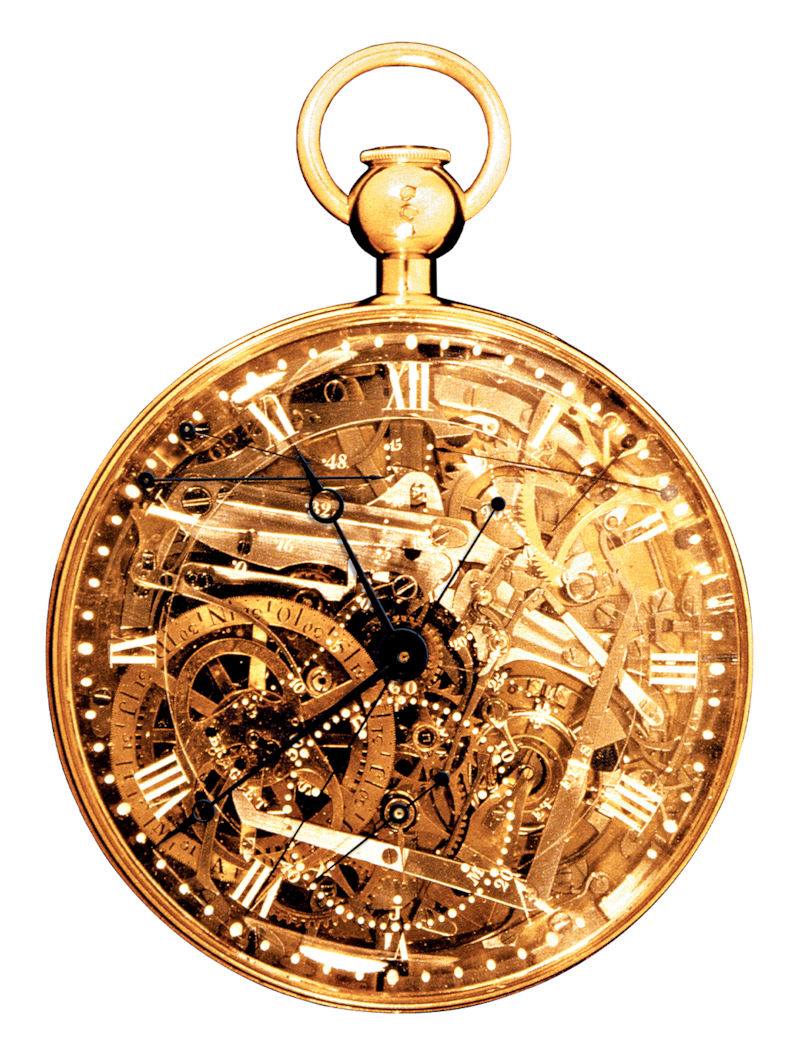

Completion of the watch and further enigmas

Watch No.160 was a perpétuelle watch, that is it was automatically self-winding, with an oscillating weight in platinum, endowed with the following functions and complications: minute-repeater; complete perpetual calendar indicating the day, date and month; equation of time; power-reserve indicator; metallic thermometer; large optionally independent seconds-hand; small sweep seconds-hand; lever escapement; gold Breguet overcoil; and a double pare-chute ‘anti-shock’ device. All points of friction, holes and rollers were in sapphire, without exception.

The watch had a gold case, with one dial in white enamel and another in rock crystal. The superposition and synchronisation of so many different complications, with all the calculations that implied, was an unbelievable “tour de force”. The initial contract had been amply fulfilled: it was the most complicated watch ever made, and it would remain the most complicated watch in the world for nearly a century to come. In 1827, the finished watch left the workshops; the cost of the labour alone amounted to the astronomical sum of 17,000 gold francs.

The rest of the story could have been straightforward. Far from it. Although there is no mention of its sale in the archives, the complete inventory drawn up on Antoine-Louis Breguet’s retirement in 1833 makes no mention of watch No.160. So the watch appears to have left the premises between 1827 and 1833, as on 11 March 1838, the repair books record that ‘Mr le marquis de La Groye, à Provins’ brought in ‘his perpétuelle repeating watch No.160 (…) for repair’. The marquis appears to have been the owner at this time. When did he buy it, and for how much? Did he buy it, or did Breguet give it to him? It is all an enigma: the Breguet archives, so detailed in every other respect, are completely silent on the subject.

The plot then continues to thicken: from his death certificate, we know that the Marquis de La Groye died without issue on 4 October 1837, and that he lived in Essonnes, not Provins. The Marquis de La Groye, of whose existence we know, who had lent money to Breguet – up to 30,000 livres in 1786 (which Breguet repaid in June 1795) – and who had been an officer until 1788, could not have been the same marquis who brought the watch in for repair, as by then he was already dead. It seems unlikely that the finished watch would have been delivered to the person who commissioned it all those years before, or that they would have been willing to wait forty years for it. And a delivery of this sort would certainly have left a paper trail. The real question is: why did the firm apparently attribute the purchase of the watch to a fictitious buyer? The mystery has remained unresolved to this day.

From 1838, the ‘gold watch’ stayed on the Quai de l’Horloge premises for several decades, with or without an owner. Finally, in 1887, it found a bona fide owner when it was bought by the British collector Sir Spencer Brunton. It later passed to his brother, and then to Mr Murray Mark, before entering the collection of Sir David Salomons. Sir David Lionel Salomons (1851-1925) was an engineer, an industrialist and a passionate admirer of Abraham-Louis Breguet and his works. He became a leading authority on Breguet and amassed the world’s largest collection of his timepieces. On the centenary of Breguet’s death in 1823, he loaned some 110 watches to the Musée Galliera in Paris for an exhibition.

Sir David Lionel Salomons (1851-1925) was a British engineer and industrialist who passionately admired the work of Abraham-Louis Breguet, to the extent of amassing the largest and most famous collection of his timepieces. On the centenary of Breguet’s death in 1823, he loaned some 110 watches to the Musée Galliera in Paris for an exhibition.

Up:

Musée Galliera exhibition catalogue.

Up:

Musée Galliera exhibition catalogue.

Right:

Musée Galliera exhibition catalogue.

Up:

Musée Galliera exhibition catalogue.

Right:

Extract from the production register mentioning No. 160.

Up:

Extract from the production register mentioning No. 160.

Up:

Imprisoned for months at the Conciergerie until her execution in October 1793, the Queen would never see the watch No. 160.

Right:

Imprisoned for months at the Conciergerie until her execution in October 1793, the Queen would never see the watch No. 160.

Up:

Imprisoned for months at the Conciergerie until her execution in October 1793, the Queen would never see the watch No. 160.

The highlight of the 1923 exhibition

On his death in 1925, he left the Marie-Antoinette to his daughter, Vera Bryce Salomons, and it resumed its picaresque career. The years passed, and Vera Bryce Salomons decided to found the museum of Islamic art in Jerusalem, in memory of her friend and teacher Professor Leo Arie Mayer of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a scholar of Islamic art. She donated all her collections of Islamic art to this project and chose to include the collection of clocks and watches that had belonged to her father. Thus it was that in 1974 the Marie-Antoinette watch, a masterpiece of horology – designed by a young Swiss watchmaker and probably intended for an Austrian archduchess who had become queen of France – became part of the collections of the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem, founded by a benefactor from a highly distinguished British Jewish family who was anxious to give a higher profile to Islamic art.

Nine years later, disturbing news shook the world of luxury watchmaking: on Saturday, 16 April 1983, the L.A. Mayer Museum had been raided when it was empty of visitors and not properly guarded, and its collection of clocks and watches had been stolen; naturally, the Marie-Antoinette had disappeared. The years passed, and despite the efforts of Interpol, the whereabouts of the stolen items remained a mystery. Speculation was rife, and numerous articles and studies were published, all declaring that any hopes of ever seeing the vanished watch were slim. The New York writer Allen Kurzweil even constructed a novel around it, titled The Grand Complication.

LE PETIT TRIANON AND NICOLAS G. HAYEK

LE PETIT TRIANON AND NICOLAS G. HAYEK

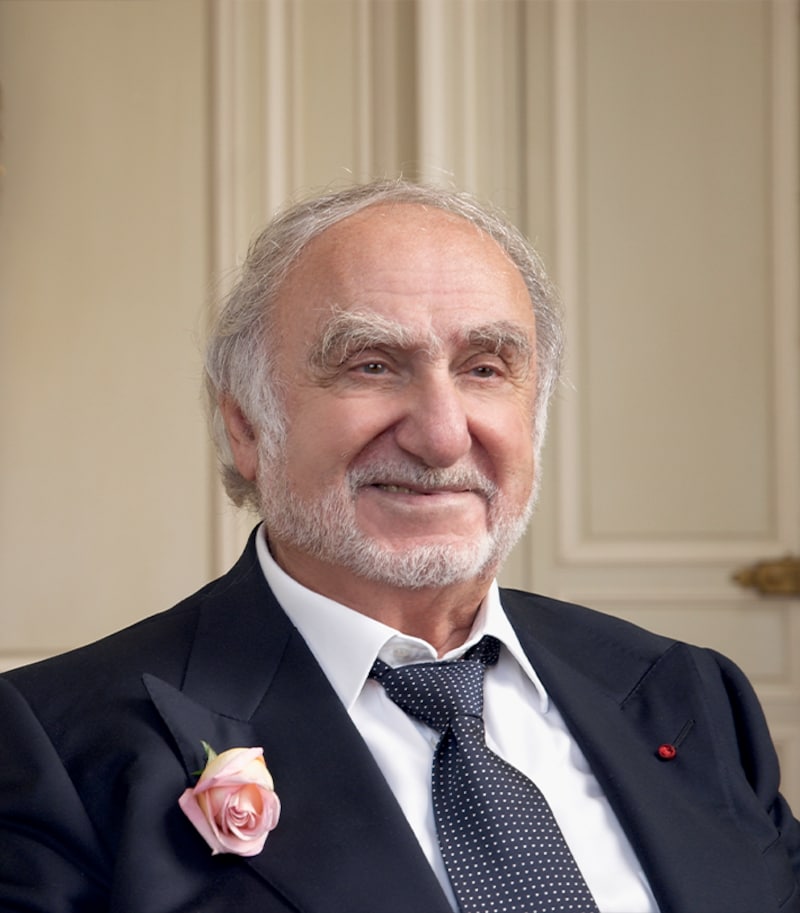

A love of art and beauty impelled Nicolas G. Hayek to seek ways of preserving historical and cultural heritage beyond the realm of watchmaking, through prestigious patronage endeavours imbued with emotion. The most emblematic of them all was undoubtedly the restoration of the Petit Trianon, an eloquent tribute paid by Breguet to Queen Marie-Antoinette, a sincere admirer and faithful client of the House.

The challenge set by Nicolas G. Hayek

In 2005, Nicolas G. Hayek, who had bought Breguet in 1999, decided to create a replica of this masterpiece: the newly revived house of Breguet would rise to the challenge. A solid technical team was assembled, and they gathered all the existing documentation. The project progressed at a steady pace, and the re-created watch was presented to the press in 2008.

Symbolically, it lay in a sumptuous inlaid oak box carved from Marie- Antoinette’s favourite oak tree at the Petit Trianon. Meanwhile, on 14 November 2007, a news story picked up by the world’s press revealed that the watches and clocks stolen in 1983 had been found, including most notably the Marie-Antoinette – twenty-four years after it had been stolen and 224 years after it had been commissioned. We now know that the man behind the robbery was Naaman Diller, a notorious Israeli thief who died in 2004. Shortly before his death, he told his wife Nili Shamrat about the heist and confessed that the stolen treasures, which were far too famous to be sold on the market, were still hidden away in bank vaults in Europe and America. It was Shamrat who was behind the restitution of 2007. While Breguet watch No.160 returned to its place in the L.A. Mayer Memorial Museum (now called the Museum for Islamic Art) in the old city of Jerusalem, the reconstructed masterpiece bore witness to the strength of Breguet’s attachment to its history, with all its repercussions, both symbolic and tangible. The decision to create a replica of

this legendary piece of watchmaking

history led to Versailles, its trees and the Petit Trianon, neglected and waiting for a generous patron.

For Nicolas G. Hayek, this represented a way of paying tribute to Queen Marie-Antoinette, who through her many purchases launched Breguet’s reputation at the start of his career. The long-awaited complete restoration of the façades and interior decor of the Petit Trianon and the French Pavilion was entirely financed by Montres Breguet and its Chairman as part of an exemplary patronage programme. The work that involved many different trades was completed in September 2008, recreating the backdrop of the Queen’s happiest years and offering visitors a chance to admire one of the most exquisite examples of European artistic heritage.

In 2005, Nicolas G. Hayek, who had bought Breguet in 1999, decided to create a replica of this masterpiece. Deprived of No. 160, Western horology must take on the challenge and Breguet in particular had a duty to do so.

Up:

The “Marie-Antoinette” timepiece was recreated by drawing on ancestral skills using period tools and techniques such as for wood-polishing the gear trains.

Right:

The “Marie-Antoinette” timepiece was recreated by drawing on ancestral skills using period tools and techniques such as for wood-polishing the gear trains.

Up:

The “Marie-Antoinette” timepiece was recreated by drawing on ancestral skills using period tools and techniques such as for wood-polishing the gear trains.

Up:

Symbolically, the watch lays in a sumptuous inlaid oak box carved from Marie-Antoinette’s favourite oak tree at the Petit Trianon.

Right:

Symbolically, the watch lays in a sumptuous inlaid oak box carved from Marie-Antoinette’s favourite oak tree at the Petit Trianon.

Up:

Symbolically, the watch lays in a sumptuous inlaid oak box carved from Marie-Antoinette’s favourite oak tree at the Petit Trianon.