Type 20 and Type XX Chronographes

by Jeffrey S. Kingston

What keeps movement designers up at night? Guesses come flying in. It must be creating one of the grand complications like a perpetual calendar, or a minute repeater. Granted, designing and building a minute repeater is one of the greatest challenges in watchmaking and perpetual calendars require clever designs to ensure that the Februarys all come out right. Movement designers, however, are quick to point to chronographs as one of the most difficult watchmaking constructions to create. History backs this up. For decades, a wide swath of the top prestige watch houses avoided producing their own chronographs in house, relying instead on Breguet’s classic 2310 (later 2320) movement for their chronographs. The obstacles and the costs were too great to do otherwise. That, of course, but also the 2310 had established itself as a reference point for chronograph design and became the haut de gamme chronograph movement of choice for much of the top watch world.

The goals that Breguet set when it undertook to develop a new movement for the Type 20 and Type XX vividly illustrate the challenges and obstacles that movement designers confront in chronograph construction. Ensuring that during start/stop of the chronograph there is no jumping of the chronograph seconds hand. Avoiding any fluttering of the chronograph seconds hand when running. Minimizing the effect on the watch’s chronometry when the chronograph is running. Designing the return to zero so that all three indications – seconds, minute counter, and hour counter – move smartly, absent any harshness, and simultaneously. Building a flyback system that operates smoothly unaffected by the force applied by the user to the bottom button. Achieving a high power reserve with a 5 Hz frequency of the movement. These are all demanding criteria that place any chronograph that meets them at the pinnacle in the watch world.

Breguet devoted four full years to achieving every one of these goals for the new Type 20/Type XX. Two closely related calibers were the product of this effort: the caliber 7281 for the two register (small seconds and minute counter) military style Type 20 and the caliber 728 for the three register (small seconds, minute counter, hour counter) civilian Type XX.

Breguet set an ambitious set of goals in designing the new Type 20/XX: No jumping of the chronograph seconds hand upon

start/stop; no fluttering of the hand when running; minimal effect on the watch’s chronometry with the chronograph running; swift return to zero of all hands with no harshness and independent of the force applied to the pusher; 5 Hz movement frequency.

The Connection

Here is a fundamental concept that, with a rare exception,1 underlies all chronographs: the chronograph elements of the seconds hand and counter hands are connected to the running train of the watch when the chronograph is operating and disconnected when the chronograph is stopped. These connection and disconnection operations are fraught with watchmaking challenges. Many chronograph designs accomplish the connection by mating two gears (a watchmaker would call them “wheels”) together. However, since the starting of a chronograph is an entirely random event, the joining of gears may not always be the ideal of the point of the tooth of one gear fitting exactly into the trough of the other. It may be that at the instant of the connection the gears come into contact with each other tooth to tooth. Result: an unattractive jump of the chronograph seconds hand. Clever geometry may ameliorate this effect to a degree, but never eliminates it entirely.

¹The Breguet Tradition Chronographe Independent is that extremely rare exception. Its chronograph elements are always entirely separate from the regular running train of the watch; the chronograph portion of the movement has its own power spring, balance wheel and gear train; all of these completely independent from the main portion of the movement with its winding barrel, balance wheel and gear train. Thus, there never is a “connection” or “disconnection”.

So how is this solved?

The calibers 728 and 7281 use what is called a “vertical clutch”. One disk of the clutch turns constantly with the watch’s running train. When the chronograph is not operating, the second disk, which drives the chronograph components, is held away from contact with the first disk by two fingers. When the upper chronograph button is depressed, the two fingers are pulled away, and, pushed by a small tripod spring, the two disks come into contact with each other and the chronograph starts running. Completely eliminated is the risk of a jump as with two gears mating. A smooth start guaranteed always.

That, however, is not the end of the story. In the system with two gears coming together, there is a second problem. Inevitably, with the tooth of one gear sitting within the trough of the second, there will be a degree of play. The result: flutter (which watchmakers term “chevrotement”) in the motion of the chronograph seconds hand. Watchmakers have traditionally solved that problem with a friction spring working against the chronograph seconds hand. Although that is, in most cases, effective in limiting flutter, it imposes a load upon the running of the watch when the chronograph is operating. That load affects chronometry. Precision is lost.

Even though vertical clutch chronographs have now been adopted by the most prestigious watch houses, not all designs are equal. Almost all the other designs employ a friction spring which creates drag adversely affecting chronometry. Breguet’s design avoids this drag effect on chronometry as it has no need of a friction spring.

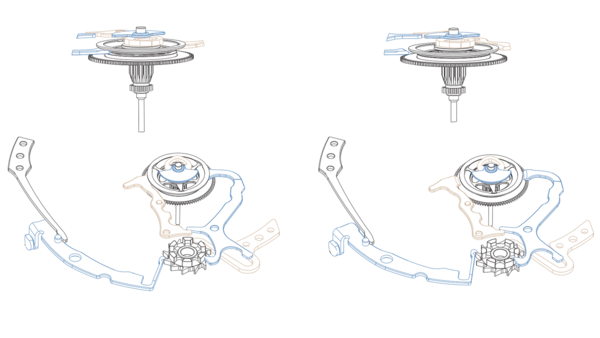

Vertical clutch

The Type 20/XX movement uses a vertical clutch to connect the chronograph elements to the movement’s running train. Shown above, the two plates of the clutch are separated by two arms when the chronograph is not running.

Below, the arms are pulled away from the upper clutch plate when the chronograph is started, allowing the upper plate to contact the lower plate, which is directly driven by the running train.

With a well-designed vertical clutch, there should be no need of a friction spring. Eliminating the spring allows the chronometry of the watch to be largely unaffected when the chronograph is operating. This is the case with the new Breguet movements.

However, almost all of the vertical clutch designs found on the market, including prominent prestige brands, utilize a friction spring so that running the chronograph does negatively impact the watch’s precision. Why? Because it is more convenient and less expensive to locate the vertical clutch away from the center of the watch. Thus, there is a gear train running between the clutch and the chronograph seconds hand, necessitating a such a friction spring. Moreover, with these offset designs, the lack of perfect precision from this additional gear train may lead to rate errors of as much as half a second during periods when the chronograph is operating. Breguet avoided these pitfalls by centrally locating the clutch and, thus, there is neither a friction spring nor an additional gear train.

Summary: The Breguet design ensures perfect engagement of the chronograph with no jumping, operation free of flutter of the seconds hand, and only minimal effect on the precision of the watch.

The return to zero system

When the owner commands a return to zero, the push of the button releases a spring which activates the return. The operation does not depend on the force of the owner’s push of the button, since it is the spring that launches the operation.

All chronographs are built with a cam shaped like a “heart”, which upon the command of a button push, returns the seconds hand and counter hands to zero. The genius of the heart shaped cam’s shape is that when a flat arm (called a “hammer”) is pushed against it, the cam rotates so as to place its top next to the hammer. That position, of course, is the zero position.

Are there ways to refine and elevate this basic design? To make the motion of the return consistent, irrespective of how hard the return to zero button is pushed? To make all of the chronograph indications – seconds, minute counter, hour counter – return to zero together? Breguet’s new calibers emphatically answer these questions “yes”.

The secret to achieving a consistent return to zero absent harshness is found with springs, two, in fact. When the owner commands the return to zero, the push on the lower button, moves an arm past a holding pin. This allows an already tensioned spring to push the arm (called the “linear hammer”), carrying the hammers forward into contact with the heart shaped cams. Thus, the force of the owner’s push only serves to release the spring and it is the force of the spring that controls the hammers. As the arm propelled by the spring carries the hammers together (two for the Type 20; three for the Type XX) all the chronograph hands return together. Breguet added one more refinement. The hammer for the return of the chronograph minute counter hand is in the form of a flexible blade which guards against undesirable play of the hand.

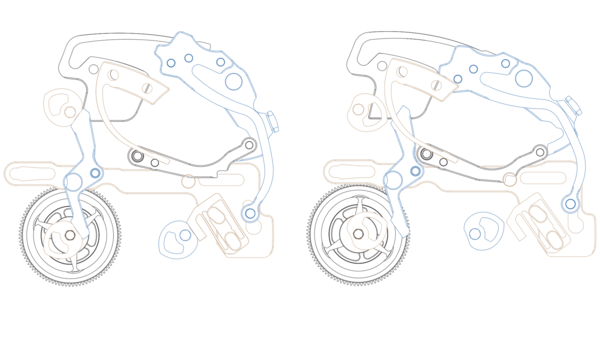

There are two other aspects of the chronograph that merit attention. First, as should be the case for any chronograph of breed, the operation of the chronograph is controlled by a column wheel. Thus, when, for example, a start is initiated by the upper button, the push serves to rotate the column wheel so that its pillars can move the elements of the chronograph, in this case pulling out the fingers of the clutch. This is a classic design approach that endows the pusher with a more sophisticated feel than other designs where the push directly operates the elements.

Up:

The column wheel being fitted into the movement.

Right:

The column wheel being fitted into the movement.

Up:

The column wheel being fitted into the movement.

Although the original Type 20 was created to fulfil the specifications of the French air force, there was a civilian version as well, the Type XX. Both modern versions, Type 20 and Type XX, fit today’s lifestyle.

Up:

Today's Breguet Type XX, reflecting the style of its ancestor, is easily recognizable in that it boasts three registers (small seconds, minute counter, and hour counter) in contrast with the Type 20 military version's two registers.

Right:

Today's Breguet Type XX, reflecting the style of its ancestor, is easily recognizable in that it boasts three registers (small seconds, minute counter, and hour counter) in contrast with the Type 20 military version's two registers.

Up:

Today's Breguet Type XX, reflecting the style of its ancestor, is easily recognizable in that it boasts three registers (small seconds, minute counter, and hour counter) in contrast with the Type 20 military version's two registers.

Second, the Type 20 and Type XX are both flyback chronographs. The flyback function is an essential for navigation and is part of grand aviation tradition. Timing segments of a flight is a fundamental pilot skill.

Typically, flight segments are defined by fixes, a location determined visually by a landmark on the ground or by radio or GPS navigation aids. When passing a fix, pilots are trained to note the time from the previous fix and start a timing event for the next segment. With a simple chronograph, three operations would be required: a push on the upper button to stop the chronograph; a second push on the lower button to return to zero; and, finally a third push on the upper button to start the next timing. A flyback construction greatly simplifies the operation. A single push on the lower button will stop, return to zero and restart. Three pushes become one, lessening the pilot’s workload.

The Base Movement

To this point our focus has been on the chronograph elements. Turn now to the core of the movement. The movement’s running rate is 5Hz, which, because it divides each second neatly into tenths, is ideal for powering a chronograph. Normally, there is a price to pay for a fast beat, a lower power reserve. The logic is easy to understand; with each beat of the escapement, there is a small unwinding of the mainspring. The more rapid the beats, the faster the mainspring unwinds. Breguet addressed the power reserve by equipping the barrel of these two calibers with a high energy density mainspring. The result: a 60 hour power reserve. Winding is bi-directional with the rotor fitted with ceramic bearings. Its form visible through the clear case back features arms which recall the form of

an aircraft’s wings.

The core chronograph functions of start, stop, and return to zero, are all commanded and controlled by a column wheel as should be the case for any chronograph of breed.

Up:

The column wheel component with its distinctive dark color and the black oscillating weight in gold.

Type XX Chronographe 2067

The new generation of Type 20 and Type XX was initially introduced in stainless steel. These models are now joined by a Type XX version in rose gold.

The balance is suspended beneath a full balance bridge. Of course, it is free sprung with gold regulation screws ensuring resistance to rate changes from shocks. Both the hairspring and escape wheel are fashioned in silicon. Not only does silicon resist magnetism, but its light weight reduces the effects of gravity upon the timepiece’s chronometry.

The fortunate owner of one of these new Breguet’s may not consciously think about its sophisticated vertical clutch design, or its column wheel, or the springs which operate on the return to zero, or the silicon hairspring and escapement. Instead, he will simply notice that start/stop occurs with no jumping of hands, that the hands move without flutter, that the return to zero of all indications occurs simultaneously and without harshness, and that both chronograph pushers operate positively and smoothly. In short, the satisfaction of a no compromises thoughtful design.